A Conversation

with Monica Aasprong

The title of your work "Soldatmarkedet", in all its deconstructions, is the core of the text itself – graphically and associatively. What was it about this word that drew you in, back when you first started, and what about it keeps the ball rolling?

The work Soldatmarkedet (Soldiers’ Market) was partly an attempt to approach the horror of the so-called war on terror, and could also be – this has come to me later – a way to process the history of my native town, Kristiansund, which was bombed heavily by the Germans in 1940. I heard these stories from my grandparents, who were brutally affected. They didn’t really like it when I moved to Berlin at the turn of the millennium, and I think this engrained in me some kind of ambivalence towards the German language.

I found the word “Soldatmarkedet” in Dag Solstad’s novel 16.07.41, from 2002. It’s Solstad’s translation of a placename in Berlin, the Gendarmenmarkt , which is located in front of Schinkels Konzerthaus. A “gendarme” is a kind of military police, and I was struck by the ambiguity of that word, soldatmarkedet, something between market and military, between economic and military power. When I came across the word I had recently moved back to Oslo. The September 11 attacks had just taken place, but as I didn't follow the news that much – I lived quite a contemplative life in Berlin, read the Bible, went to concerts – I was quite confused when I came back to Oslo, turned on the radio, and heard that the US and UK was waging war on Afghanistan. I found it very disturbing and impossible to understand that this terror attack from Al-Qaeda could motivate a full-scale invasion and bombing of a country where some of the terrorists involved in the attack might be staying. I thought of all those soldiers sent to this faraway place, by almost all the NATO countries, as the war progressed.

At the time, it was as though many of my different experiences got mixed together. There are lots of soldiers in the Bible, in the Gospels as well as the Old Testament, and when I read about this escalating war on terror – soon it reached Iraq as well, with the terrible bombings of Baghdad in April 2003 – it struck me how we usually follow war at a distance, be it in time or space, that it is related somehow; very remote and very present at the same time – although still worlds away from the people actually experiencing the reality of war. The word Soldatmarkedet, the soldier's market, keeps on begging questions.

In the text, which has had many iterations and reproductions – a chapbook, a poetry collection, readings, exhibition displays, etc. – you vacillate between different modes of language and different aesthetic methodologies, echoing principles of concrete poetry as well as concerns of a more semantic, literary kind. What’s your approach to the process of writing/creating, and what’s your experience working with and juxtaposing contrasting traditions and poetic concepts?

To me, this vacillation is totally natural. I don’t view different ways of writing as contradictions or dichotomies, although that has often been the case, such as with the concretist movement in Sweden in the 60s, or with the literary objectivists in the US in the 30s. But even if one proclaims a desire to strip language of transcendence, to see the words as objects without semantic implications, I think there’s an inherent ambivalence in these movements. When it comes to practice, it’s difficult to present a single element of language, be it a letter or a word, without there being associative implications for the reader/listener – regardless of the writer’s intentions. I don’t think there’s a contradiction between so-called conceptual or systemic poetry, and other, more traditional, lyrical genres. All genres are conceptual in some way. Rather, the choice is between going into a traditional structure or trying to conjure one up, in order for it to carry across your experience, questions, and wonderings.

In my case, the different approaches to the term “Soldiers’ market” were ways to explore how image and text are treated and presented in our time. How they are transposed. To see what might happen if image and text were to converge, how they might influence each other, and to let them split, like information are split in a lot of media outlets. And when I say image I mean text as image, as abstraction.

If you don’t view the conceptual and the literary as opposites, but rather as parts of a whole, they still operate with different entry points, or emphases, that influence or define their potential as tools. Can you give any examples of the intention behind specific approaches used in this book? Did this intention translate into the result, or did it change along the way?

When writing, I found that I couldn’t really control how it was working, whether it be the nature of the interaction between text as image and text as sound, or simply the text as text – such as the long poem which became a collection published by N.W. Damm & Søn in 2006. My intentions were varied and hard to sort out, but one reason for splitting up the work in different formats was to handle the media revolution; the way written sources (along with images and music) were becoming increasingly digitalized – this was just starting out at the turn of the millennium. Another reason was a wish to explore what would happen to a literary work which resists overview, one that you can never take in all at once – how would the fragments work on their own? Putting something into different contexts inevitably changes its meaning, whether the change is minor or more fundamental. Perhaps this approach was a way to express how impressions and information tends to be part of something else, something we can’t see, at least not immediately – as is the case with life itself...

As a project that has gone on for a while, and is still alive and kicking, what has this come to mean for you? Does the process itself have a focal point, or is it fundamentally experimental and explorative?

I have started working on it again recently, after a kind of hibernation – although I had no idea whether I would continue or not when I last worked on it back in 2010. In that sense it’s fundamentally explorative. Somehow the different approaches relating to form and media invites this openness; it can’t really be defined. The project is related to my other works, Circle Psalm (2013), and Mnemosyne Nomenclatur (2018), which also deal with the infinite and the arbitrary.

As for the focal point of Soldatmarkedet, these other works are essentially concerned with memory and history, and the question of who is in the position to speak, to define, to interpret – and from which media outlets, which platforms, which sources. How do we express ourselves? What is passed on, and how?

History is always changing, slowly or swiftly – as we see with post-colonial and feminist perspectives gradually challenging established perspectives. Part of the reason this project resurfaced, in addition to the war in Ukraine, was as a reaction to the strange media climate which seems to have forgotten about all the other brutal wars that we, the west, have been directly involved in. It’s as if we’ve never experienced war before. Perhaps it’s because the other wars have been so far away from us geographically, but I don’t think any international jurisdiction can be credible without comparative thinking. Today it’s almost a crime to be anti-militarist; we believe that weapons are the solution, that “weapons will lead to peace” as Secretary General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg puts it. Polish-German activist and philosopher Rosa Luxembourg went to prison several times before and during WWI because she opposed the war. She asked questions you weren’t supposed to ask, such as “who’s being sacrificed? Who’s profiting? What’s the imperialist logic behind the will to keep the war going? Who to believe? Which media outlets, which narratives?”

Alongside the elements of personal reflection and more general existentialism , there’s a strong core of politics in your work. What are your thoughts on the relationship between politics and abstract/experimental/non-linear work? How can the work have a political purpose while embracing ambiguity and discovery?

I'm not sure if I would say the work has political purpose – except perhaps to arouse political awareness, to provoke some questions in the reader or the listener. I think that an abstract expression, non-linear, and, above all, non-discursive, can have the possibility to do this – I mean: a lot of the information we get from the press about war has to do with what kind of weapons are being sent, number of deaths (even though this is classified, and as such, inaccurate) – and what kind of information is that, really? Is it giving us more precise knowledge, or an accurate impression of what is going on? Of the mental implications for each soldier, for the generations of people affected? Of their feelings, mental state, experiences of hatred, sorrow, loss, and so on? I'm not sure that so-called fact-based information is more effective in revealing the truths about war and violence than an abstract or poetic expression. Of course, my expression is not comparable with someone who is directly involved, we all express ourselves based on context, both geographical and temporal. Which is true when it comes to our experience of art as well as our experience of a news report. As a reader or spectator, our position in time and space, and a lot of other parametres, influence how we relate. We have to take responsibility for our attitudes, thoughts and feelings. I don't think poetry or art should try to affect this in a direct way, but it can possibly spark these questions within the reader – “with music as a guide”, as the Palestinian poet Somaya al Sousi so beautifully put it.

After a while, I moved towards a more tactile expression with Soldatmarkedet. I started working with gouache paint , and then with handwritten text. The printed sheets seemed to ask for that, especially the 16000 permutations, which were automatically generated, printed out and put in an archive, a steel cabinet, for an exhibition at Skulpturens hus in Stockholm in 2005. In hindsight I see this iteration of the work as a way of dealing with the technological evolution towards what we now call AI. This installation was a collaboration with media engineer and artist Eric Sjödin, who contributed to the technological part of the work, making the program that generated the permutations from my original sheets. The material in this cabinet has been re-used in several ways, to make books, diptychs, scrolls etcetera.

Many aspects of the project have changed over the years, and I now have new perspectives on the project’s earlier parts. But from the very beginning, the title itself outlined how the work revolves around the link between war and economy, state and individual, and I try to bring these questions to an existential and emotional level, to say something about loss, about power, and the lack thereof.

About the work

Image 1, 2, 5

process, private

Image 3

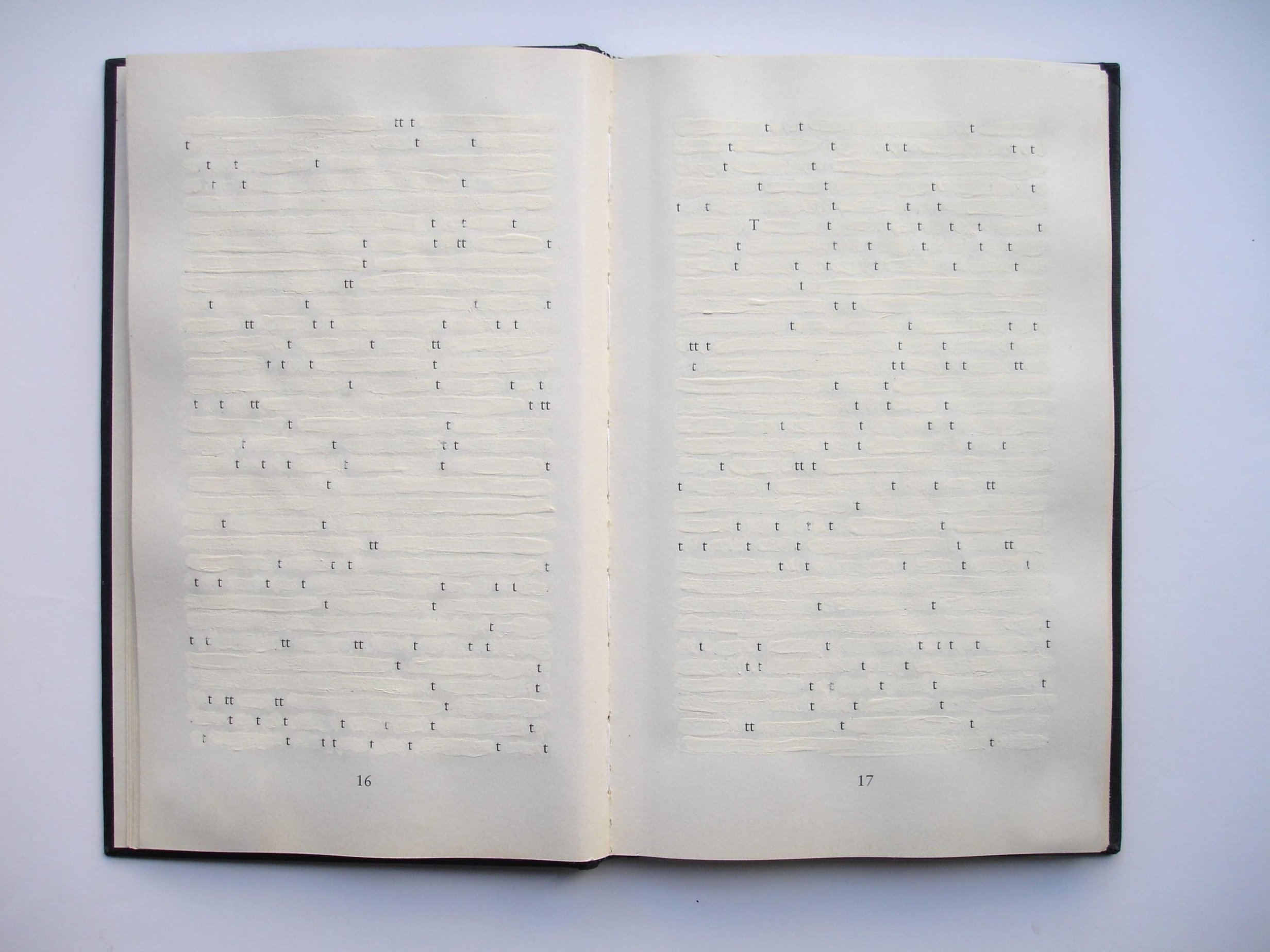

Soldiers’ Market, 2006.

Image 4

Soldatmarkedet, N.W. Damm & Søn, 2006

Image 6, 7

In process; handwritten copy of a digital scroll, published on Nypoesi 2/06

Image 8

Book published at Oslo International Poetry Festival, 2007

Image 9

Soldiers’ Market, Skulpturens Hus, Stockholm 2005

Image 10

Tripthych, interactive installation at Babel Art Space, Trondheim, 2007

About the artist

Monica Aasprong (b.1969 in Kristiansund, Norway) is a Norwegian poet living in Stockholm. Aasprong works with installations and audio works as part of her authorship, and has been a post graduate student at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. As well as a novel, essays and librettos, she has published four poetry collections; Soldatmarkedet/Soldier's Market (2006), Et diktet barn/An Invented Child (2010, Sirkelsalme/Circle Psalm (2013) and Mnemosyne Nomenclatur (2018. Together with two colleagues she founded the literary journal LUJ in 2002.