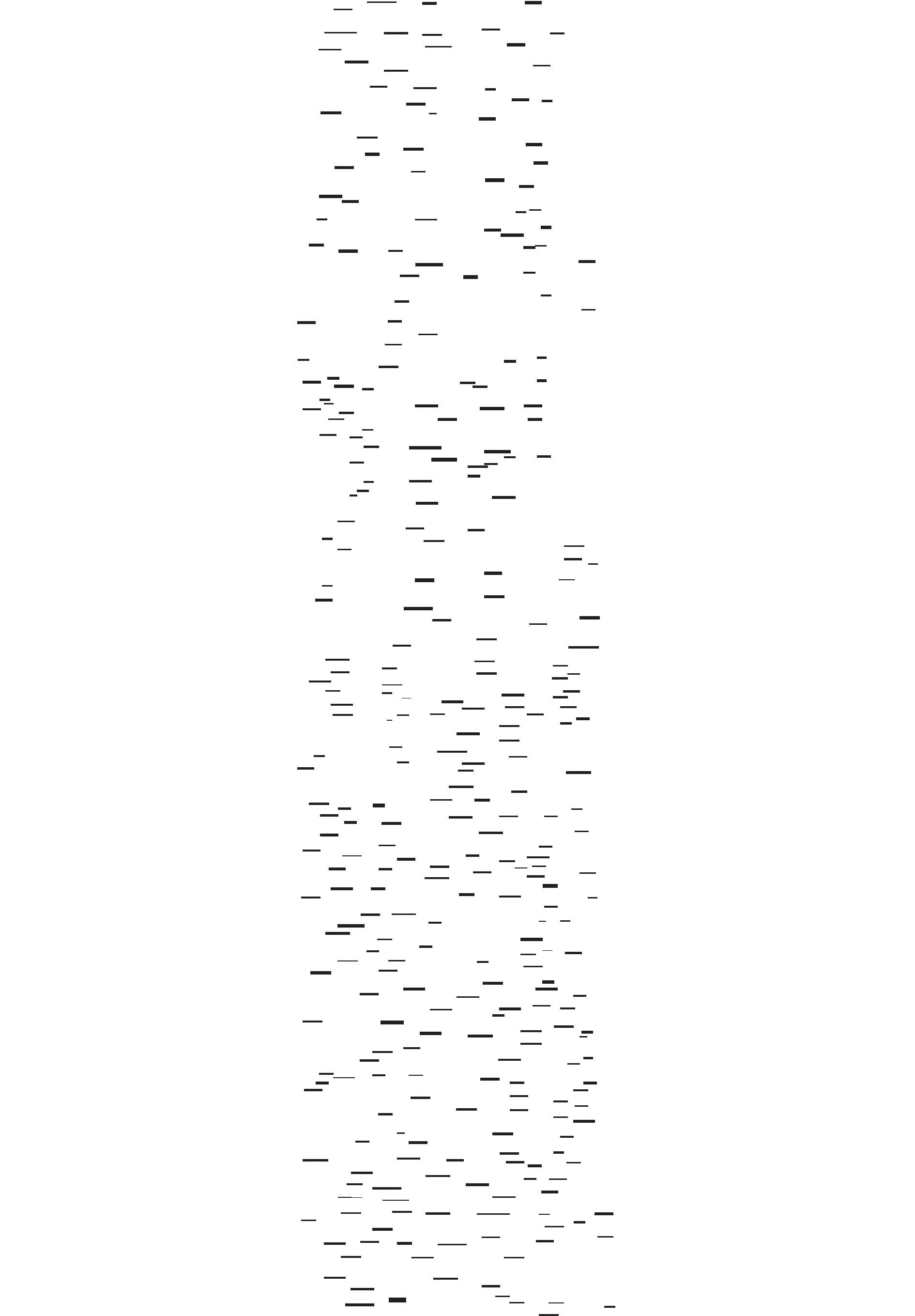

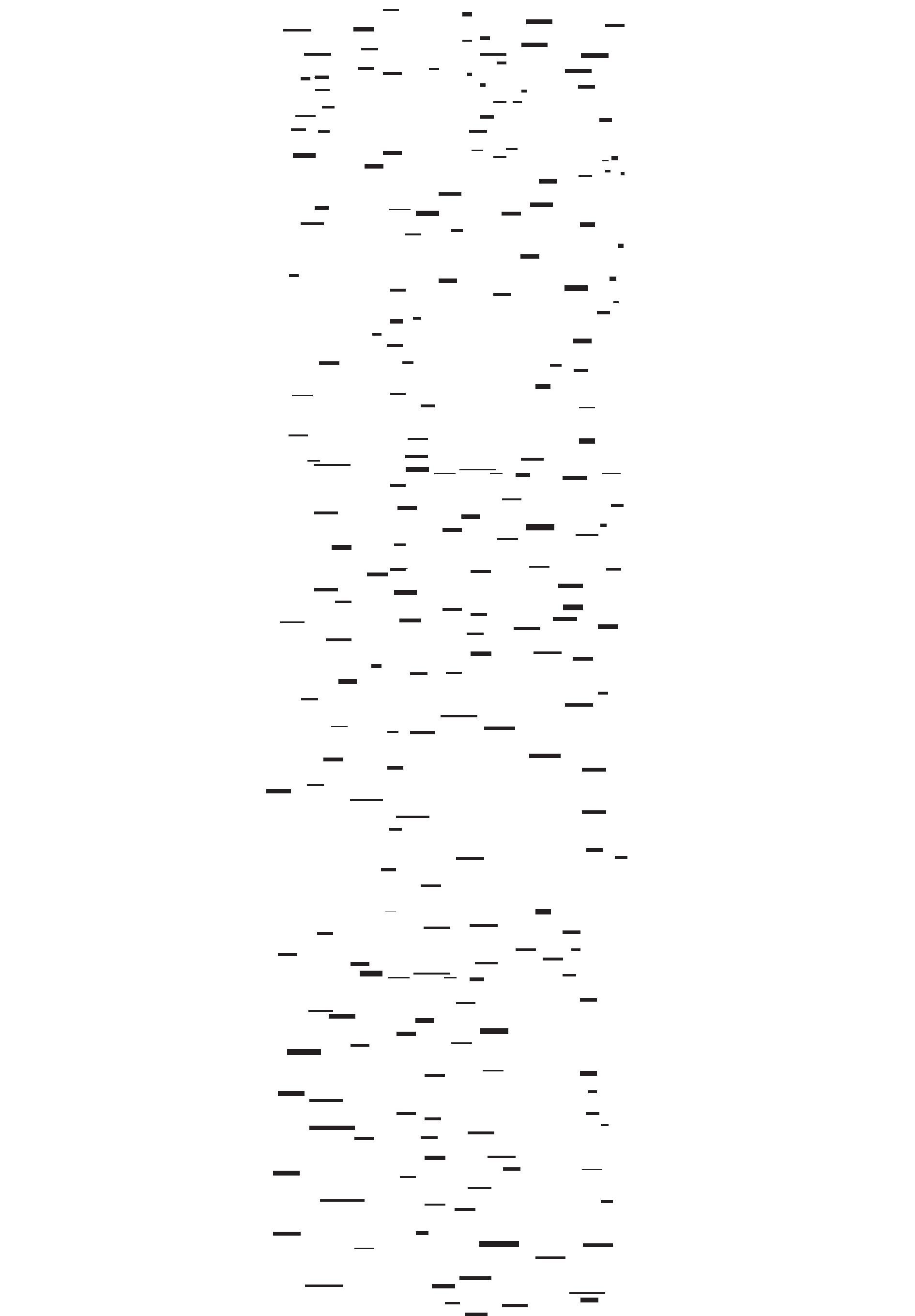

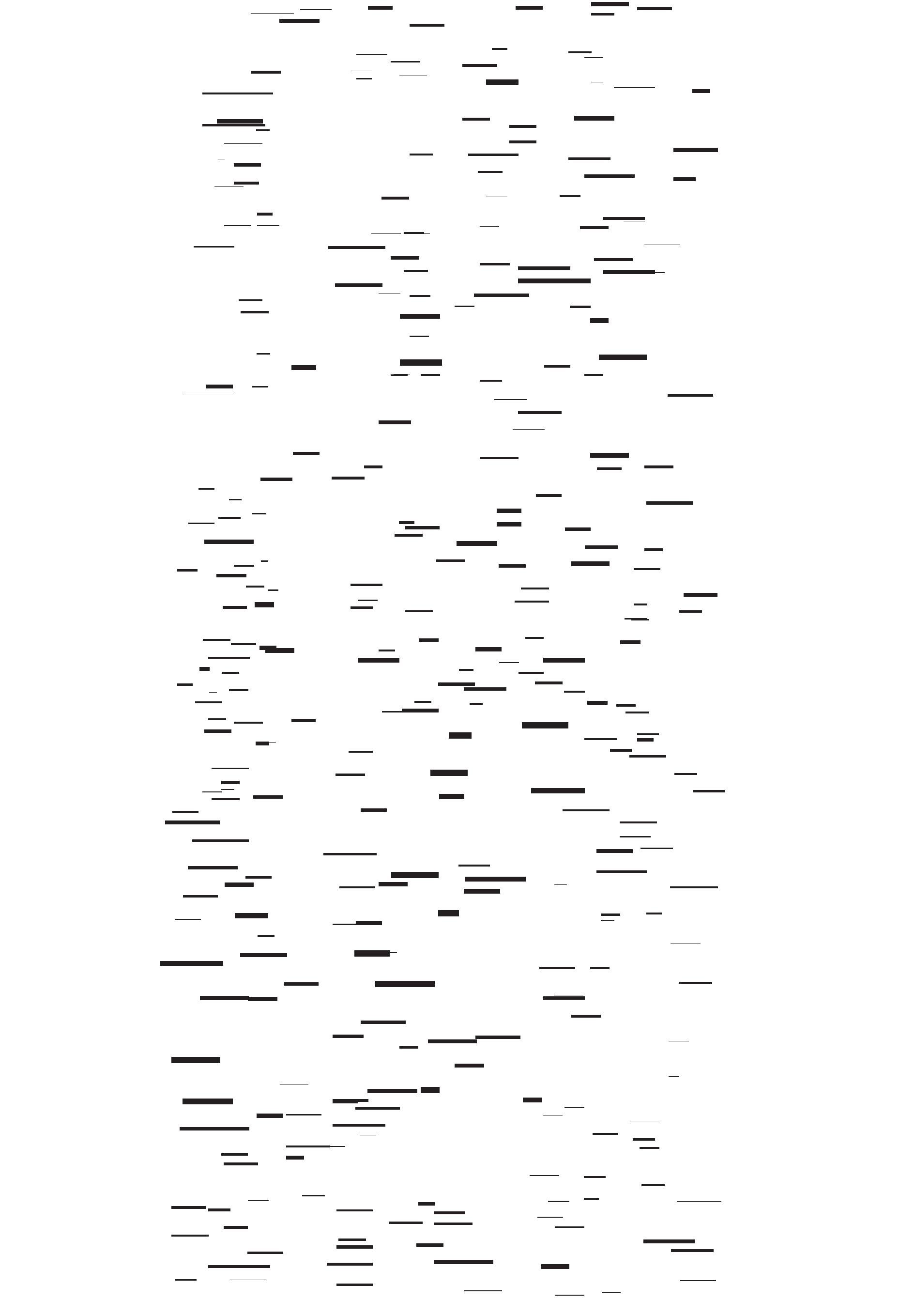

A Piece by Kamilla Jørgensen

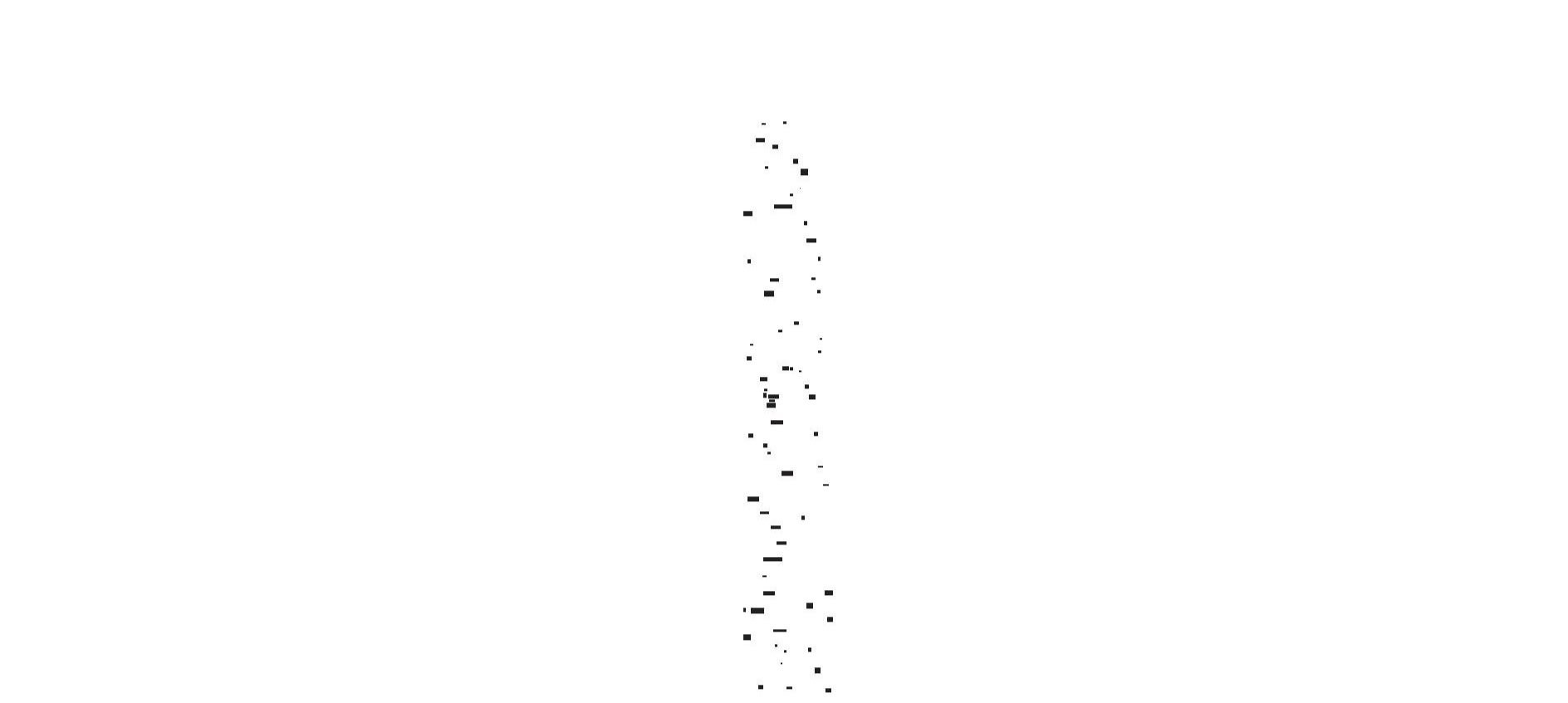

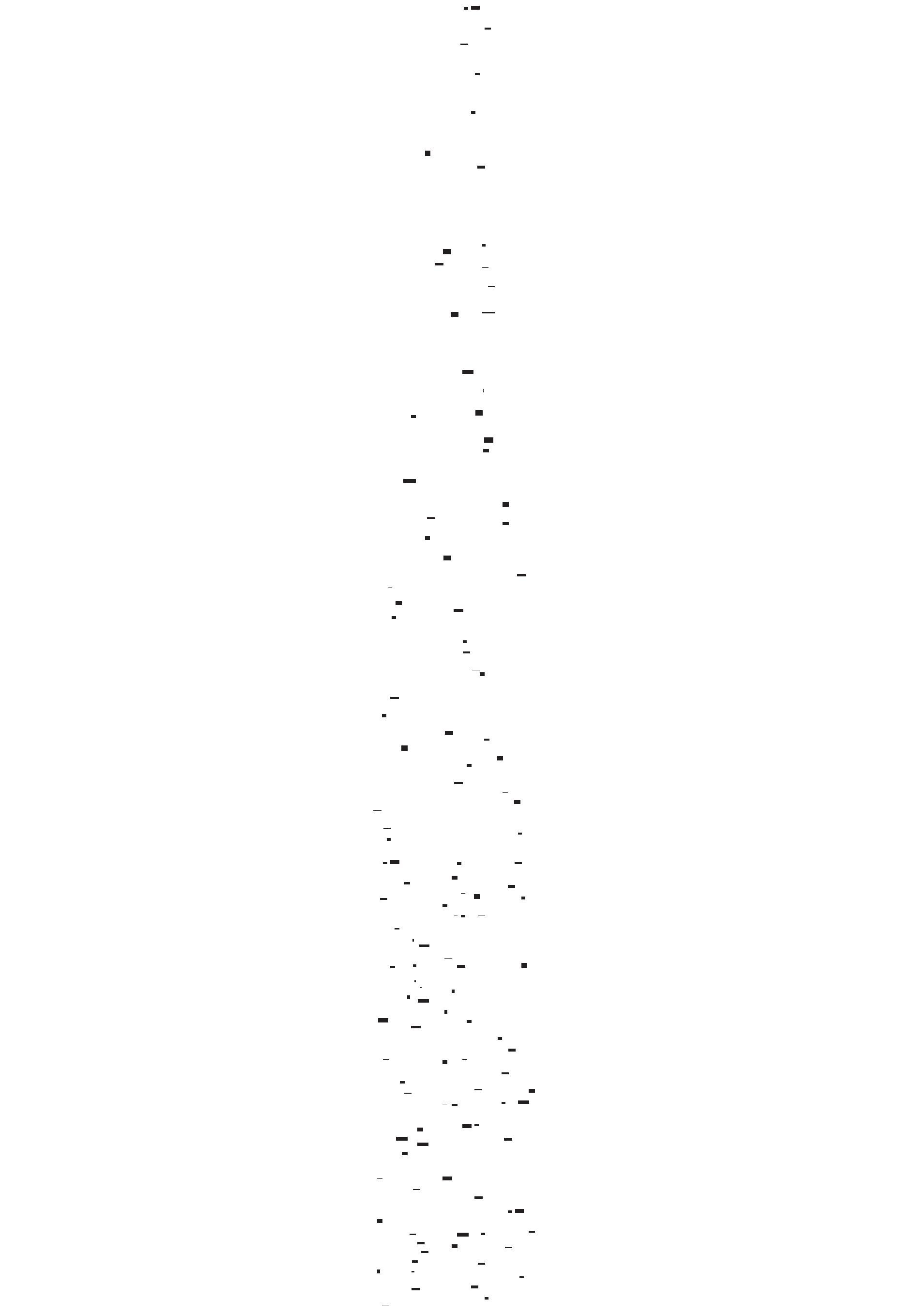

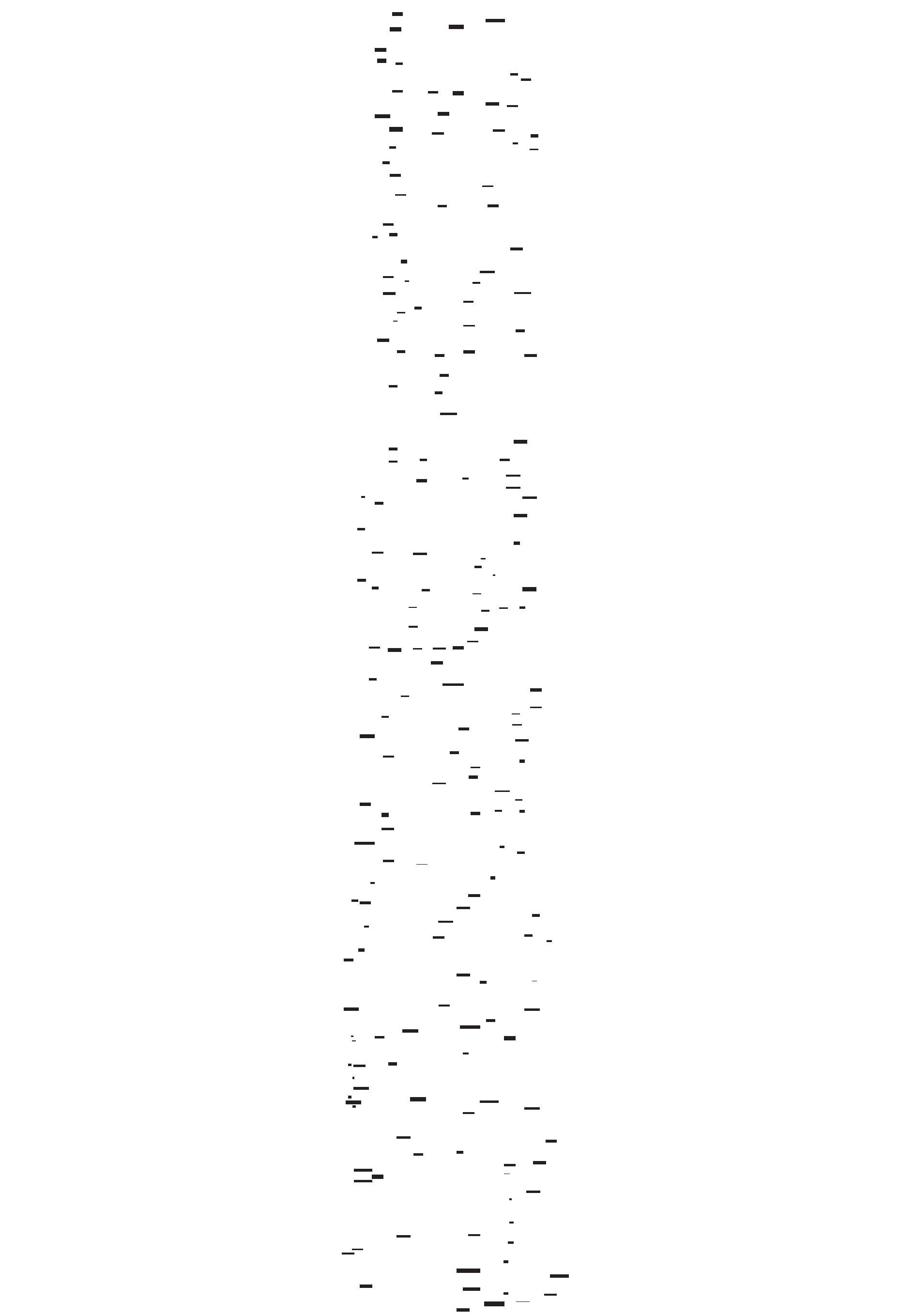

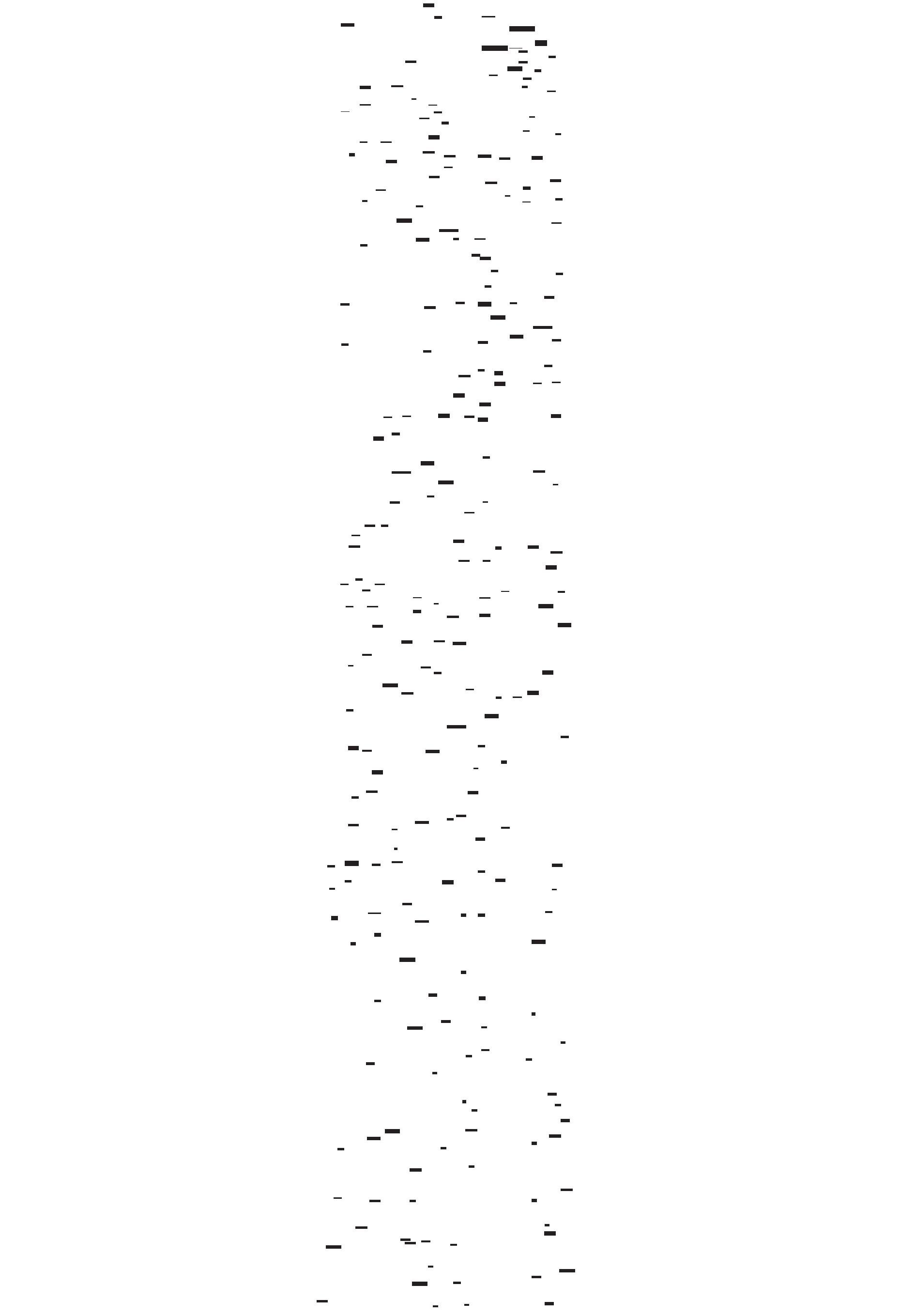

A Downey beech stands in my garden; 420 centimetres tall, with a base circumference of 16 centimetres. It has black lines in its bark called lenticels (from Latin, Lenticularis, small lens,) or raised pores. The pores of this particular tree are inscribed on here in a scale of 1:1.

The tree should be read from the bottom up, which I imagine is the correct reading direction for a tree. The trunk is oldest at the bottom. This is the tree’s first page. But really it can be read any way you choose, from the top downwards, or from the bottom up. Or one or another way round. Here it is read from the top. I’ve made a vertical delineation of the trunk to separate the text and enable it to lay flat on the screen.

Lenticels are found in many kinds of bark, but against the white skin of the birch, the black pores are particularly distinct and resemble writing on paper. In summer they function as windows, creating an oxygen exchange between the interior of the trunk and the surrounding air. In winter, the tree closes them.

The breathing windows echo erasure poetry’s articulation. The black bars on the white background recall Man Ray’s Poème Optique/Lautgedicht (Optical poem/Vocal poem) from 1924, or Marcel Broodthaers’ homage to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard/A Thrown of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance, 1897. Broodthaers crossed out Mallarmé’s words and transformed the poem into an abstract image that still appears as language and called it Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard. Image, 1969.

Birch bark is well-suited to writing. There are numerous examples of Ancient Buddhist texts and letters in Russian on birch bark. The oldest known text is from the13th century, in Finnish. But the birch also writes on itself, tattooing its skin in a radical form of self-annihilation, a black censor bar, an erasure technique also called redaction that brings to mind the censoring of secret-stamped documents, a diary or a long poem written in Asemic script, or an aural poem drawn by the in- and exhalations of the tree, read by the wind.

Translated from Danish by Phillip Shiels

Bark

”Brat endevendt, læst helt ud

i sin yderste, inderste bladfold

af et gennemgribende vindstød ...”

Asketræet læst af Per Højholt

fra Det gentagnes musik

I min have står en dunbirk, 420 centimeter høj og 16 centimeter i omkreds ved roden. Den har afsat sorte streger i barken, såkaldte lenticeller (lat. lenticularis, lille linse) eller barkporer. Netop det træ med de barkporer er aftegnet her i størrelse 1:1.

Træet skal nok aflæses nedefra og op, som jeg forestiller mig er den korrekte læseretning af et træ. Stammen er ældst forneden. Det er træets side 1. Men egentlig kan det vel læses, som man vil, oppefra og ned, nedefra og op. Den ene eller den anden vej rundt. Her læses det oppefra og ned. Jeg har lagt et lodret snit langs stammen for at skille teksten ad, så den kan lægge sig fladt på skærmen.

Lenticellerne findes i mange slags bark, men på birkens hvide hud fremtræder de sorte barkporer særligt tydeligt og ligner skrift på papir. Porerne fungerer som vinduer og sørger for iltudvekslingen mellem stammens indre og den omgivende luft i løbet af sommeren. Om vinteren lukker træet sine vinduer.

Disse åndende trævinduer har slettepoesiens udtryk. De sorte bjælker på hvid baggrund ligner Man Rays digt Poème Optique/Lautgedicht (Optisk digt/Lyddigt) fra 1924, eller Marcel Broodthaers homage til Stéphane Mallarmés digt Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard/Et terningekast vil aldrig afskaffe chancen, 1897. Broodthaers har overstreget Mallarmés ord og transformeret digtet til et abstrakt billede, der stadig fremstår som sprog, og kaldt det Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard. Image, 1969.

Birkebarken er velegnet til at skrive på. Der er fundet gamle buddhistiske tekster og russiske birkebarksbreve. Den ældst kendte tekst er skrevet på finsk omkring 1200-tallet. Men birken skriver også på sig selv, tatoverer sin hud med en radikal form for selvudslettelse, en erasureteknik med sorte bjælker (redaction på fagsprog), der leder tanken hen på censurering af hemmeligt stemplede dokumenter, en dagbog eller et langdigt skrevet med asemisk skrift, eller et lyddigt tegnet af træets ind- og udåndinger og læst af vinden.

Original text by Kamilla Jørgensen

About the artist

Kamilla Jørgensen (b. 1969, in Copenhagen) is a Danish writer, translator and text-based visual artist with special interest in conceptual writing and artist books. Her publications are often combined with a sculpture or an exhibition that concretize the material in the book.